Key Takeaways

HIPAA compliance requires adherence to three main rules: Privacy Rule, Security Rule, and Breach Notification Rule, with the Privacy and Security Rules having the greatest operational impact on practices

Risk assessments must be conducted on all digital systems owned by covered entities using structured frameworks like NIST SP 800-30, with nine specific elements required by the Department of Health and Human Services

Business Associate Agreements (BAAs) are mandatory legal contracts extending HIPAA obligations to third-party vendors, making full compliance unavoidable for functioning practices

Administrative, physical, and technical safeguards form the Security Rule foundation, with modern cloud-based tools making implementation more achievable than it appears

Civil penalties range from approximately $100 to $50,000 per violation across four tiers, with potential criminal charges carrying up to 10 years imprisonment for malicious violations

Intro: Understanding the Basics of HIPAA Compliance

As the leader of a practice, you don’t need to be an expert in every line of the health insurance portability and accountability act (HIPAA) regulations, but you do need to understand the basics to make smart decisions.

HIPAA, briefly defined, serves as the foundational privacy and security regulations for health information technology in the United States. The law comprises three main rules that structure compliance obligations:

The Privacy Rule governs how and when protected health information can be disclosed, establishing patient rights and organizational responsibilities for information handling.

The Security Rule mandates specific administrative, physical and technical safeguards to protect electronic protected health information (ePHI) stored or transmitted by covered entities.

The Breach Notification Rule defines what constitutes a reportable breach and establishes notification requirements when unauthorized access occurs.

A key insight is that HIPAA compliance isn’t a prescriptive checklist, and it never could be. Entities that must comply with HIPAA come in so many sizes and organizational patterns that no regulatory body could ever create a list of to-dos that encompass every scenario. Instead HIPAA is a collection of regulations that are effectively asking you to balance Confidentiality, Integrity, and Availability (CIA) of protected health information (PHI).

Health and Human services (HHS) expects each covered entity to assess risk and create controls commensurate to its operations. This risk-based approach means that a small family practice and a large health system will have different implementations of the same underlying requirements, but both must demonstrate systematic attention to protecting individually identifiable health information.

Title 45 is a large regulatory text that governs public safety at a federal level. The text is broken into several subparts and subchapters, with various federal agencies having dominion over the portions of the regulation that they have statutory authority over. The Department of Health and Human services has statutory authority over Subtitle A. Under this subtitle we find Subchapter C, which is the locus of most HIPAA regulatory language.

HIPAA compliance can generally be though of as adherence to Parts 160, 162, and 164 under Subchapter C. Within the regulations, we find 3 overarching “HIPAA Rules” that structure most compliance obligations. The Privacy Rule and the Security Rule will have the greatest bearing on your business operations, as they contain the largest share of required, regularly occurring activities.

Note that HIPAA implementations come in both “required” and “addressable” form. Required are those things that must be in place from day one, while addressable items can be implemented as part of longer-running plan, or have documented justification for why they aren’t applicable in your specific case. Consider reading this article to learn about the System Security Plan (SSP) approach.

It’s crucial to understand that “addressable” does not mean optional—it means practices must justify not implementing a given control, or have a concrete plan that they follow.

If the entity you manage fits the definition of a Covered Entity in the Subpart C regulatory text, you are legally bound to comply with HIPAA. Covered entities include health plans, healthcare clearinghouses, and healthcare providers who transmit health information electronically. The scope is broader than many realize—even small practices that use electronic health records or submit electronic claims are typically covered entities.

Business associates became directly liable under the HITECH Act of 2009. This brought about the concept that there must be an agreement detailing each party’s responsibility in protecting PHI between covered entities and the service providers they engage with—these agreements are called Business Associate Agreements (BAA).

BAAs further bind your operations to HIPAA requirements, because you will eventually need some service that requires you to sign a a BAA—e.g., Google Cloud services or HIPAA-compliant messaging apps. This creates a web of compliance obligations that extends throughout the healthcare ecosystem, making complete compliance with HIPAA unavoidable, no matter the size and maturity of the operation.

HIPAA Privacy Rule: How and When PHI Can be Disclosed (45 CFR Part 164 Subpart E)

The basic purpose of the Privacy Rule is to govern how protected health information and electronic protected health information can and should be disseminated.

The Privacy Rule requires documented policies and controls governing how protected health information is used, shared, or disclosed within and outside your organization.

Core principles include patient consent for most disclosures, minimum necessary use (limiting access to only what’s needed for specific purposes), patient rights to access or amend records, and accounting of disclosures for six years.

These privacy principles create the need for small and large practices alike for secure messaging systems, formal record release procedures, and comprehensive staff training programs.

Operationally, compliance is mostly achieved through documented policies and procedures that specify when staff can access or share patient information, how to handle patient requests for records, and what constitutes appropriate authorization for non-routine disclosures.

The complete regulation can be viewed at the Privacy Rule text.

HIPAA Security Rule: Required PHI Protections (45 CFR Part 164 Subpart C)

For ease of understanding, we are splitting this rule into subsections, as the HIPAA Security Rule encompasses multiple categories of security measures.

All systems and software owned and managed by a covered entity must have these safeguards in place, even if they will never store electronic protected health information. For example, In cases where a system will never contain electronic protected health information, compliance might be as simple as noting in policy documents that electronic protected health information must never be on said system, and the training can briefly state that policy. However, the system is indeed in HIPAA scope simply because the covered entity owns and manages it.

The complete regulation can be viewed at the Security Rule text.

Administrative Safeguards

Administrative safeguards are the policies, procedures, and governance processes that manage the selection, development, implementation, and maintenance of security measures. These safeguards ensure that the right people have appropriate access to systems and that everyone understands their security responsibilities.

The administrative safeguards include 9 standards, with specific required and addressable implementation specifications for each:

Security Officer designation (required)

Workforce training and access management (required)

Information access management (addressable)

Access authorization procedures (addressable)

Workforce clearance procedures (addressable)

Information system activity review (required)

Security incident procedures (required)

Contingency plan development (required)

Regular security evaluations (addressable)

Security roles like that of the HIPAA Security Officer can be contractors and don’t necessarily need to be employees, allowing leaders the flexibility to have a more medical-focused staff and hire qualified firms like S5T to perform these duties.

However, those designated security roles must receive unwavering support from leadership—if the security officer says “no” to something, that has to stand, even if it was an owner they said no to.

Training is also a recurring requirement—not a one-time event. Everyone handling protected health information must complete annual training and sign policy acknowledgments. Documentation of all acknowledgements, policies, risk assessment, and training must be retained for at least six years.

Technical Safeguards

Technical safeguards focus on technology and how it is configured to protect electronic protected health information and control access to it.

The technical safeguards include 5 standards:

Access controls with unique user identification (required)

Audit controls and activity logging (required)

Integrity controls to prevent improper alteration (addressable)

Person or entity authentication (required)

Transmission security for data in transit (addressable)

With modern cloud-based tools and platforms, achieving all these technical safeguards is more possible than it seems on the surface, particularly if you are working with a firm that has a strong background in building compliant systems and procedures.

Modern cloud-based tools have come a long way, and users will not have a burdensome experience using HIPAA-hardened systems when properly implemented.

Physical Safeguards

Physical safeguards protect the physical facilities and equipment where electronic protected health information is stored or accessed. These safeguards ensure that unauthorized individuals cannot gain physical access to systems or data.

The physical safeguards include 4 standards covering:

Facility access controls with locks, badges, and visitor procedures (addressable)

Workstation use policies and procedures (required)

Workstation security and device security (addressable)

Device and media controls for asset management and disposal (required)

Many of these physical safeguards that are required for workstation use, as well as workstation and device security are accomplished automatically when a qualified provider implements the security controls of technical safeguards.

Devices can be attached to centralized and cloud-based endpoint management systems and identity management systems that together also control physical access ipso facto.

For example, enabling and centrally requiring two-factor authentication protects a physical laptop from being logged into by anyone who shouldn’t be logging into it, and requiring disk encryption means that even if someone ran off with the laptop, they could never read what is on the hard drive.

Breach Notification Rule: What Happens When Things Go Wrong (45 CFR Part 164 Subpart D)

The Breach Notification Rule establishes what must happen when there is unauthorized access to or disclosure of protected health information. These rules specify who must be notified of a breach, when notifications must occur, and what information must be included in breach notifications.

Notification requirements stipulate timelines for when notification must happen based on the number of individuals’ data involved in the breach, but also who must be notified. The HHS Office for Civil Rights (OCR) Secretary must always be notified, as well as the affected individuals, but in cases where more than 500 individuals are affected in a given state or jurisdiction, prominent media outlets must also be notified. Details can be found at the HHS breach reporting guidance page.

Importantly, notification is only required for unsecured protected health information breaches, giving you discretion in whether you need to report the breach based on risk assessment and the nature of the unauthorized access. Examples where reporting may not be required include:

Risk assessment outcomes showing a low probability of compromise

Unintentional acquisition by authorized workforce members acting in good faith

Cases where it can reasonably be determined that those who gained access to the protected health information cannot retain it

More details about these exceptions can be found in the HHS breach notification guidance.

The complete regulation can be viewed at the Breach Notification Rule text.

HIPAA Risk Assessment Requirements (45 CFR 164.308(a)(1)(ii)(A))

Every digital system owned by a covered entity—even those not storing protected health information—must undergo risk assessment, no exceptions. This foundational requirement drives most other security measures and demonstrates your systematic approach to identifying and managing security risks.

Conducting risk assessment needs to be a structured and thorough process, so using a framework is highly advisable. There are many frameworks to choose from, like NIST CSF, RMF, HITRUST CSF, and more, each with their own unique approach to organizing and conducting comprehensive security reviews.

No matter which framework you choose, there is generally going to be some high-level set of steps you follow beginning to end and then document your findings along the way. This documentation becomes crucial evidence of your due diligence and systematic approach to compliance.

HHS defines nine elements of a risk analysis that must be present:

Scope of the Analysis – Clearly define which systems, data, and processes are included in your assessment, ensuring you cover all areas where electronic protected health information might exist

Data Collection – Gather information about your current systems, data flows, access controls, and existing security measures to understand your current state

Identify and Document Potential Threats and Vulnerabilities – Systematically identify what could go wrong, from technical failures to human error to malicious attacks

Assess Current Security Measures – Evaluate what protections you currently have in place and how effective they are at mitigating identified risks

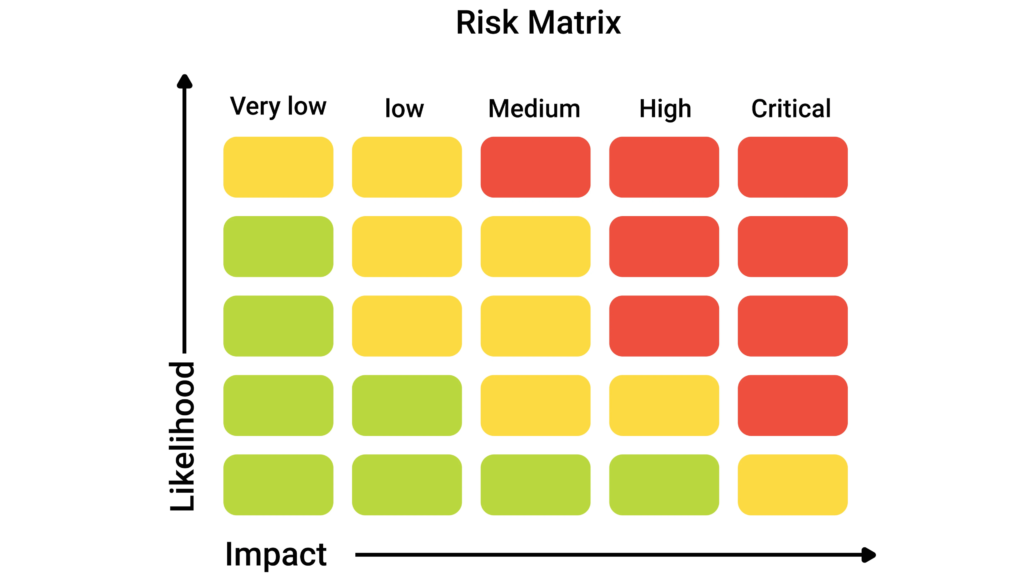

Determine Likelihood of Threat Occurrence – Estimate how probable each identified threat scenario is, considering your environment and existing controls

Determine Potential Impact of Threat Occurrence – Assess what would happen if each threat materialized, including operational, financial, and reputational consequences

Determine Level of Risk – Combine likelihood and impact to prioritize risks and guide your remediation efforts toward the most critical areas first

Finalize Documentation – Create formal documentation that demonstrates your methodology, findings, and planned responses to identified risks

Periodic Review and Updates to the Risk Assessment – Establish a schedule for reviewing and updating your assessment as your environment changes or new threats emerge

The HHS frequently cites the NIST SP 800-30 publication as a recommended guide for risk assessment implementation, and this publication is free to use and will scale from the smallest practices all the way up to large ones.

The complete regulation can be viewed at the risk assessment requirement.

Business Associate Agreements (BAAs) and Requirements (45 CFR 164.504(e))

A Business Associate Agreement is a legally binding contract that defines the responsibilities of business associates with respect to protected health information under HIPAA. These agreements are required anytime a third party accesses, stores, or transmits protected health information on behalf of your practice.

Third parties requiring business associate agreements include everything from vendors to cloud service providers, to 1099 contractors. Common examples include billing software companies, email service providers, cloud storage services, software and web developers, healthcare providers working as 1099 contractors, and analytics providers.

The BAA defines the security responsibilities of each party and legally binds each party to those responsibilities. By simply signing a business associate agreement with anyone, you are also legally binding yourself to fully adhere to the HIPAA Security Rule requirements in their entirety.

Because of the wide scope of applicability, your business will never be able to function without signing a business associate agreement at some point. This means that even if the HHS definition of a covered entity somehow did not apply to you and bind you to HIPPA compliance—and that wouldn’t ever be the case, to be clear—a business associate agreement soon will.

There are also due diligence requirements for each party with regards to business associate agreements, including reviewing security policies, confirming that compliance training is in place, verifying they have breach notification procedures, and ensuring they have adequate risk management and audit practices in place.

The complete regulation can be viewed at the BAA requirements.

Real World BAA Example: Google Cloud BAA

In the case of Google, the end user agreements that you sign when using their products mandate that, if you are a covered entity, you must sign their business associate agreements or not use their services. This requirement demonstrates how pervasive business associate agreements have become in modern healthcare operations.

Google has a standardized business associate agreements covering Google Workspace and the Google Cloud Platform. This means services like Google Workspace or Google Drive can achieve HIPAA compliance if a business associate agreements is signed and configurations meet the required controls.

There are a multitude of security configurations that must be implemented in these Google services, and doing so will become your responsibility, per the business associate agreement. Google is merely taking responsibility in the BAA to make these configurations available on their platform.

This is important to understand, as it does not mean you automatically have a HIPAA-compliant, Google-based information system simply because you signed the Google business associate agreement.

The business associate agreement creates the legal framework, but proper implementation requires systematic configuration and ongoing management of security controls, ideally by a qualified professional.

Using NIST Publications to Guide HIPAA Compliance

As the author mentioned previously, HIPPA requirements lack detailed technical instructions, so NIST frameworks can help fill that gap with concrete guidance for implementing required security measures. These publications provide the technical depth that HIPAA rules intentionally leave flexible.

NIST 800-66 provides guidance on implementing HIPAA Security Rule safeguards with specific technical recommendations and implementation approaches that have been tested across thousands of organizations.

NIST 800-30 provides a framework for conducting the risk assessments required by the HIPAA Security Rule with step-by-step methodology that ensures you meet the nine elements required by HHS, while creating documentation that will withstand regulatory scrutiny.

NIST 800-53 offers a more detailed checklist for cybersecurity hardening with comprehensive security controls that can be mapped directly to HIPAA requirements and scaled appropriately for different organization sizes.

Small practices should use these as roadmaps to facilitate strategic and well-organized compliance progress, knowing that the programs these frameworks help them put in place will scale larger than they may ever care to grow. This approach ensures that initial compliance investments provide long-term value and adaptability.

Enforcement and Penalties

HHS’ Office for Civil Rights enforces civil money penalties for HIPAA violations, while DOJ handles criminal cases. Understanding the penalty structure helps practices appreciate the importance of systematic compliance efforts and the potential consequences of neglecting their obligations.

The four-tier civil penalty structure outlined by the AMA includes:

Tier 1 – Lack of knowledge – Approximately $100 – $50,000 per violation for situations where the covered entity did not know and would not have known of the violation by exercising reasonable diligence

Tier 2 – Reasonable cause (not willful neglect) – Approximately $1,000 – $50,000 per violation for situations where the violation was due to reasonable cause but not willful neglect

Tier 3 – Willful neglect, corrected within 30 days – Approximately $10,000-$50,000 per violation for situations involving willful neglect that was corrected within the required time period

Tier 4 – Willful neglect, not corrected within 30 days – Approximately $50,000 per violation for incidents stemming from willful neglect that was not corrected

It is worth noting that you will not qualify for tier 1 by stating that you are not tech savvy, or that you didn’t really understand your regulatory responsibilities. The “exercising reasonable diligence” part of that bullet means that you should have acquired expert compliance help if you didn’t or couldn’t understand these things, and you needed to adhere to what they said if you did hire them.

There are also cases where criminal charges can be filed by DOJ. One could be imprisoned for up to 10 years when HIPAA violations are committed with the intent to use protected health information for commercial advantage, personal gain, or malicious harm, as explained by the ADA in this article.

These penalties underscore why systematic compliance programs focused on risk management, staff training, and vendor management are essential investments rather than optional expenses for healthcare organizations.

Conclusion

HIPAA compliance can appear intimidating, but practice leaders do not need to become regulatory experts to manage it effectively and make side decisions. What they do need is a firm grasp of the fundamentals: the three HIPAA rules, the centrality of confidentiality, integrity, and availability, and the fact that HIPAA is ultimately a risk-reduction-focused regulation, not a rigid cybersecurity or operational checklist.

By understanding how the Privacy Rule governs the use and disclosure of PHI, how the Security Rule translates into administrative safeguards, physical safeguards, and technical safeguards, and how the Breach Notification Rule applies when things go wrong, you can make informed decisions instead of reacting in crisis.

Structured risk assessments, thoughtful use of Business Associate Agreements, and disciplined training and documentation practices form the backbone of a defensible compliance program.

NIST publications and similar frameworks exist to help you turn abstract requirements into concrete actions, scaling from a small practice to a complex health system.

Likewise, modern cloud platforms and managed services, when properly configured, make it increasingly realistic for even modestly sized practices to meet security expectations without stifling operations.

Enforcement and penalty structures underscore that HIPAA is not optional. Civil and, in some circumstances, criminal consequences are real, but so is the opportunity: well-run compliance programs not only reduce regulatory risk, they also improve operational discipline, data quality, and patient trust.

If you treat HIPAA as an ongoing risk management discipline—rather than a one-time project—you will be far better positioned to protect your patients, your staff, and your practice as it grows.

FAQ

How often should covered entities update their HIPAA risk assessments?

While the Security Rule requires “ongoing” risk assessment without specifying exact frequency, best practice is to conduct comprehensive assessments annually and whenever significant environmental changes occur. This includes new systems, major software updates, changes in business processes, or after security incidents. Quarterly vulnerability scans help maintain continuous monitoring between formal assessments.

Can small practices use the same compliance approach as large health systems?

Yes, but the implementation will be scaled appropriately. HIPAA requirements are risk-based and proportionate to organizational size and complexity. A small practice might use cloud-based solutions and simplified policies, while a large system requires enterprise-grade infrastructure and extensive procedures. However, the fundamental requirements—risk assessment, safeguards implementation, staff training, and vendor management—remain the same across all sizes.

What happens if a business associate has a data breach?

The business associate must notify the covered entity without unreasonable delay and no more than 60 days after discovery. The covered entity then has its own notification obligations to patients and regulators, depending on the breach’s scope and impact. This is why due diligence in selecting business associates and maintaining strong business associate agreements is crucial—their security failures become your compliance problems.

Do HIPAA requirements apply to telemedicine and remote work arrangements?

Yes, all HIPAA rules apply regardless of where care is delivered or work is performed. Remote work requires additional attention to physical safeguards (secure home office spaces), technical safeguards (VPN access, encrypted devices), and administrative safeguards (remote work policies, training on home security). Telemedicine platforms must meet the same security standards as in-office systems and typically require signed business associate agreements.

How do state privacy laws interact with HIPAA compliance?

State laws can impose additional requirements beyond HIPAA minimums, and covered entities must comply with both federal and state regulations. Some states have stronger breach notification requirements, different patient access rights, or special protections for certain types of health information. When state and federal requirements conflict, the more stringent requirement typically applies, making it essential to understand your state’s specific healthcare privacy laws alongside federal HIPAA obligations.